While I often share critiques of graduate school for its normalized workaholism, I have to admit that attending my MA/PhD program did change my life. Being a student offered me resources and funding that independent scholars can’t easily access. I learned about queer and feminist scholarship and had brilliant, caring mentors who cheered me on, even when they learned I planned to leave academia.

Though I applied to my combined MA/PhD program to research Critical Pedagogy, I fell in love with historiography (the study of how history is recorded) my first semester in the course “Writing Women’s Histories.” The next semester, less than a year into my 7-year journey to my PhD, I stumbled upon the person who would become not only the focus of my dissertation, but also a key part of my life (and, later, a tattoo on my body): Lisa Ben.

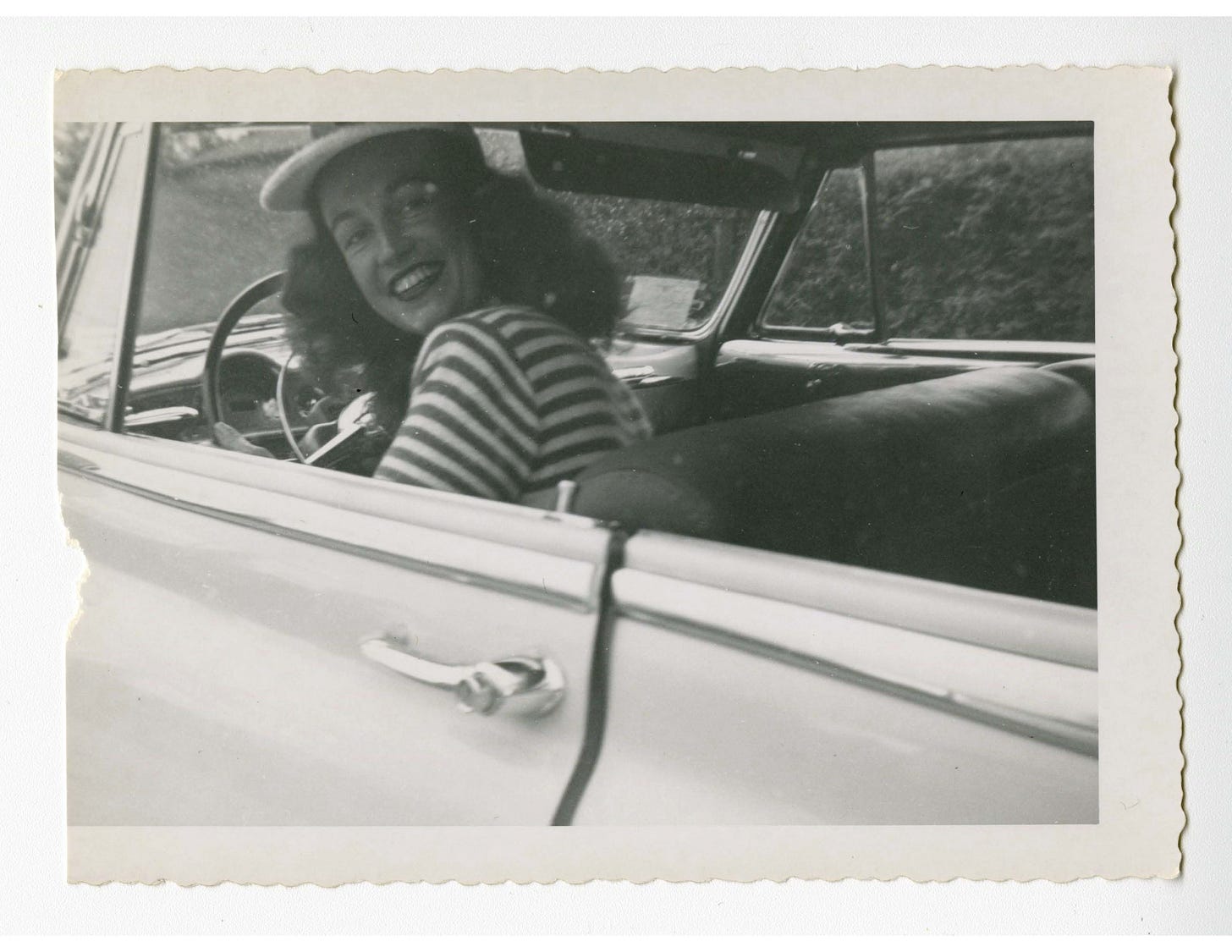

I could talk to you about Ben for days and days, but to keep it brief, Lisa Ben—an anagram for “lesbian”—is the pseudonym for Edythe DeVinney Eyde, who was born in California in 1921 and passed away in 2015. Ben was a lifelong writer and creative, a lover of horror films, and a passionate caretaker of stray cats, though she is most remembered for writing Vice Versa, the first lesbian magazine in the U.S., in 1947-1948 (a time when it was illegal to send homosexual content in the mail).

Once I decided to research Lisa Ben in 2014, I was committed to sharing her story, in awe at this queer ancestor who did such important work and somehow felt barely remembered. Since I was in a Rhetoric and Composition program, I had to situate my dissertation research on Ben within writing studies, which meant I focused on queer rhetorical analysis, rhetorical education, and contextualized Ben’s contributions alongside medical and legal discourses of the time. Fascinated by circulation studies, my dissertation examined the ways anti-homosexual discourse infiltrated popular media, including films, novels, and songs, in the 1940s through the 1960s.

Writing about Lisa Ben for my dissertation was a satisfying puzzle. I dutifully applied theoretical lenses to say something novel and poignant about history, and I am very proud of my final manuscript. And yet, however mesmerized I was about writing my dissertation, something felt off about the process. In order for my reader to comprehend why what I thought was important was actually important, I had to perform my knowledge by applying theory and constructing a complicated and jargon-heavy manuscript.

It didn’t feel like enough. So, in 2020, I created LisaBenography.com.

I did this for a few reasons:

I’m one of few people who know a LOT about Ben, having spent many years combing through her archive and researching her.

I want my research to be freely and publicly accessible to folks who don’t have institutional access to materials. I built my website and pay for the domain name and hosting out of my own pocket to make it easier for people to learn about her.

I want my research to be written without academic jargon so people outside of academia can access and understand it.

I want to share things in real-time. If I were to write an academic article about Ben, it would take a long time to write and then I’d have to wait to hear from an editor at a journal to see if they even wanted it, and then I’d likely have to edit it, and when it was published, it would only be read by a handful of people whose institution pays to access the journal.

I don’t think you need to understand queer rhetorical analysis or grasp the history of sexological discourse in order to experience the significance of Ben’s contributions. In fact, I don’t think you even need to consider her writing and her music and her artwork as contributions; you can simply think she is witty, or brilliant, or complex, or creative.

Lisa Ben did a number of things….

She wrote Vice Versa and circulated it by hand to fellow lesbians in the 1940s. She wrote fiction and poetry, commentary pieces, and reviews of books and films—all so other lesbians could have access to LGBTQ+ culture and content. You can read scanned copies of Vice Versa here.

Using the pseudonym “Tigrina,” Ben published her science fiction and horror writing in sci-fi literary magazines and was a secretary for the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. Some of Ben’s sci-fi writing is included in the anthology Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction.

Ben created original songs and queer parodies of popular songs to give them lesbian and gay characters. She performed these at parties and even recorded a 2-song record for the Daughters of Bilitis. You can listen to that record here.

Out of all of Ben’s songs, one in particular brings tears to my eyes: a parody version of the barbershop song “Wedding Bells,” originally written in 1929, that she reworked and called “That Old Gang of Mine.” You can read more about it here, but to synthesize: the original song is about a heterosexual man losing his friends to marriage and Ben’s parody uses the same rhythm and tone to sing about homosexual men being entrapped, jailed, and fined by the Vice Squad. It’s important to note that Ben performed her parody at gay parties in private homes, serving as a warning for her homosexual friends of the dangers they might encounter when they left the safety of the private space and went into public.

Ben’s song validated homosexuals’ fears of violence and entrapment while offering support via camaraderie. Imagine her gay audience listening to her version, while in the back (or front) of their minds they recalled the original version’s crooning about the “inconvenience” of marriage, partnership, and safety in homes. Whereas the original heterosexual version subtlety resists the phenomenological progression of love and family-building, Ben’s version cycles like an eerie music box, telling a dark yet credible truth: we may get entrapped, jailed, and fined for loving while homosexual.

You don’t need to know what phenomenology is to grasp the significance of what Ben was doing and why it mattered so much back then. We’re seeing similar things play out again in hateful anti-LGBTQIA+ bills in the U.S. We see it in restrictions on school curriculum like the “Don’t Say Gay” laws and in anti-trans messaging in The New York Times.

I hope that the digital archive I’m building over at LisaBenography.com honors Ben’s legacy and creates an opportunity for us all to reflect on its continued significance today. As I said in the final line of my dissertation:

I will need to make intentional choices about which discursive practices I employ across the genres I create and co-create, always with an awareness that my history of Lisa Ben itself is a rhetorical document that, if I am lucky, will continue to circulate and educate beyond my lifetime, as well.

I hope you enjoyed learning a bit about my life as a PhD student and as an independent scholar. As a special treat for folks who made it this far in today’s letter, I’d like to share that tattoo I mentioned above, which is a copy of Lisa Ben’s own handwriting in Ben’s go-to ink color: dark green. I discovered this writing on a copy of a newspaper article Ben had cut out of a newspaper in her youth and I had it tattooed over my heart in 2020.

If you’d like me to share more posts about my research interests, please let me know via a comment or an email. I’ll back back next week for the February Q&A post!

Take good care,

Dr. Kate

I love this.

Thank you for sharing your work so generously, this is fascinating! I had chills as you discussed Ben’s “This Old Gang of Mine,” your retelling hit me in a profound way.