Productivity scholars offer helpful approaches—and each person has the prerogative to choose which ones to apply to their own lives. When I’m teaching folks how to personalize their approach to their productivity practices, I encourage them to take what works and leave the rest, or adjust the tools to align with their actual levels of time, energy, and focus.

There are two steps that can help you to take what works and leave the rest when you’re learning how to use a productivity tool.

Step 1: Learn the general concept of the tool.

This might include understanding the psychological process of how the tool works, who developed it and their purpose for using it, what steps one needs to complete in order to utilize the tool, how you’re supposed to benefit from it, etc.

Step 2: Adjust it to fit your life.

Productivity tools are not one-size-fits-all, and if utilizing them causes us to experience negative self-talk or overwhelms our brains and bodies, then it might not be the right tool for us—and that’s okay. If we’re intent on using the tool, we might need to adjust our expectations and practices to use it in a way that works for us.

For example, because of the way my schedule works, I personally don’t like to assign my task list to specific time blocks; however, I do like to use co-working as a way to increase my focus on specific activities during a specific amount of time.

Instead of forcing ourselves to do something that feels bad for us, I encourage people to borrow parts of the approach and hack the process to make the tool feel more accessible. As a result, it becomes actually helpful based on their real-life schedule and energy levels.

Here’s an example of how we might do this with the Pulse and Pause approach.

The Pulse and Pause approach is a productivity tool that utilizes a focused work session (pulse) and an intentional break session (pause). A popular example of the Pulse and Pause approach is the Pomodoro Method, which alternates 25 minutes focusing on a specific task, 5 minutes taking a break, repeated four times in a row during a 2-hour work session. The purpose of using a Pulse and Pause approach is to limit distraction, increase focus during monotasking, and encourage the use of breaks.

Here are four ways you might adjust the Pulse and Pause approach to fit your life.

Adjust pulse and pause lengths based on your preferences.

There’s no rule that says you have to do 25 minutes on and 5 minutes off. Depending on your comfort or interest levels, you might endeavor to do 5 minutes of work as a way to jumpstart yourself and then take a break. If you’re doing creative work, you might want to have longer work sessions to enable you to reach a state of flow, and if you’re doing complicated or critical thinking tasks, you might prefer to take more breaks.

Measure output based on time (number of pulse sessions) for long-term projects.

When you’re working on a long-term, complicated, or multistep project, you might feel disheartened at the end of a work session if you haven’t made “visible” progress. While measuring word count might feel like a good motivator when you’re drafting, other tasks like revision, brainstorming, or reading might take more than a work session to show the fruits of your labor. In this case, measuring your progress by how many time blocks you spend on your work can give you something to check off your to-do list and prove to yourself that you are getting somewhere.

Calculate how long a task actually takes to complete to help with scoping projects.

It can be challenging to estimate how long a task will take to complete, but using a pulse session as a form of measurement can help you learn more about your practice. Without forcing yourself to overwork (we’re aiming for accessible, not overambitious!), track how far you can get with a task during a pulse session. This approach can be helpful for tasks like reading or grading student papers.

Set boundaries around how long you work on a task to increase prioritization and limit overwork.

I love to use pulse sessions as a way to set boundaries around how long I engage with a specific task, like responding to emails, researching, or writing a shitty first draft. If you have an activity that can become a time suck, try time boxing it for a length of time. You might experience increased focus due to the gamification (“let’s see how much can I get done in this amount of time”). If you have a particular task on your to-do list that can become a rabbit hole (research is a big one!), the boundary of a pulse session can help to limit the breadth and depth to a manageable level.

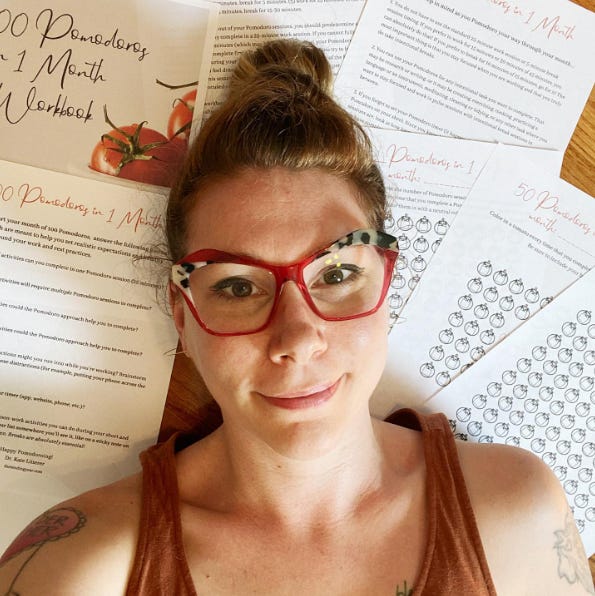

If you’re curious about using the Pulse and Pause approach, I invite you to check out a free workbook I created called “100 Pomodoros in One Month.” This workbook includes a page of journal prompts to help you strategically plan your Pulse and Pause sessions, cute tracker sheets to color in as you complete each Pomodoro, and space to record which tasks you tackled during this process.

Have a productive and also restful week, everyone!

Dr. Kate